Encouraging Your Child’s Individual Interests

When her son asked to quit basketball for more time to explore other interests, Christine Horstman was surprised to experience mixed feelings. There just wasn’t enough time for the demanding basketball schedule and the time and space he desired to nourish his creativity.

The reasoning made perfect sense. But for Horstman, it meant no longer being a “basketball mom,” an identity she’d fully embraced within the school community.

“Many parents have heard the idea of living vicariously through children,” she said. “Even if your intention is never to do so, it can sneak up on all of us. There are things we love about past school days we hope our kids will experience. Then there are things we didn’t have that we desire for them. My son’s ask shook my unspoken expectations of what his high school life would be. It turns out that what I anticipated was different than what he wanted, and I had to separate the two.”

Luckily, Horstman is a professional coach who teaches communication and emotional intelligence. She credits her background with letting go of basketball as something she’d share with her son and as one of her connections to his life.

Following Passion

As a coach, Horstman always encourages people to name their strengths, develop them, and invest in their interests. She came to realize she had to do the same for her son.

Her fears that he wouldn’t put this newfound free time to good use were quickly proven wrong. Her son tried out for the school’s one-act play competition, got one of the lead roles, and started his own rock band.

Caregivers of children in artistic endeavors can also experience a situation like that of Horstman and her son. A child might display exceptional musical talent, only to come home one day and demand dropping orchestra for a sport. Or the kiddo who paints beautiful works? She decides to toss her paintbrushes in favor of coding.

How should parents react? Horstman suggests taking an assertive communication style approach.

“When you break down communication styles, there are passive, assertive, and aggressive,” she explains. “Aggressive is I win, you lose. I’m superior; you’re inferior. The classic parent line, ‘because I said so.’

Passive means not saying what you think or not claiming your emotion. To a child, a parent might say, ‘You’re making me so mad right now, pick up your room’ versus saying, ‘I feel upset or disrespected when I ask you to pick up your room, and you haven’t.’

Then we have assertive, where you own how you feel. Rather than saying to a child, ‘You’re making me so mad right now, pick up your room,’ a parent might say, ‘I feel upset or disrespected when I ask you to pick up your room, and you haven’t.’ You express your point of view clearly and directly while still respecting others.”

Full Attention and Challenging Times

While talking with her son about giving up basketball, Horstman told him that she had actually quit high school sports and regretted it. She didn’t want him to have that feeling. At the same time, while respectfully expressing her feelings, she carefully listened to him.

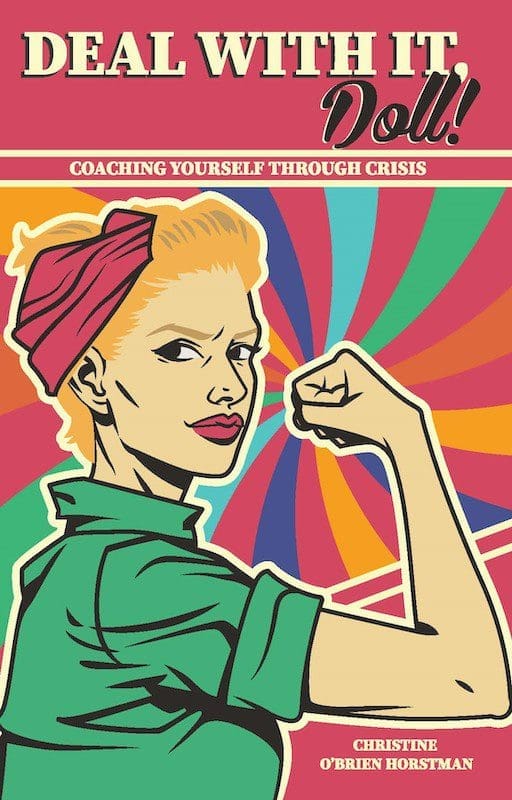

In her book Deal with It, Doll! Horstman stresses the importance of giving children time and FULL attention. If they’re taking the time to talk, parents need to stop what they’re doing and soak it in. Horstman warns that without regular communication and interactions, children may decide to shut out adults right when they need them the most.

“Kids, especially teenagers, need to know caregivers want to know them as people,” she said. “They need to know their feelings are real and important and they are loved for who they are at their core.”

The roots of Horstman’s “Deal with It, Doll!” were planted by a thyroid cancer diagnosis when her son was 18 months old. She’s lived with many chronic illnesses since then.

Writing and journaling have helped her cope. In 2021, the Writer’s Garret published her poem “The Long Haul” in its anthology. Horstman wrote the piece to help process her experience with COVID.

For her book, Horstman ends each chapter with mantras to help readers’ mindsets. There are also powerful questions that act as journal prompts.

On parenting, they include:

• What do you most want your children to learn from you?

• Do you consider your child’s success your success?

• What are your biggest fears as a parent?

• What do you admire most about your child(ren)?

“At the end of the day, parents need to remember it’s OK their kids’ dreams, interests, values, and goals may not be what they hoped for them,” says Horstman. “Acceptance is the greatest gift you can give a child.”

Christine Horstman

Website

Deal with It, Doll! Book

Instagram

Facebook

Written by Erin Prather Stafford

Top image by Ron Lach for Pexels

More Girls That Create Posts

Help Your Kids Thrive By Debunking These Myths About Resilience

When to Give Kids Their First Phone

Nurture Your Girl’s Creativity With a Daily Routine for Kids